Over the past few years, I’ve seen the same pattern repeat across different companies, teams, and stages. It stopped feeling situational and started feeling structural. Leadership changes. Direction shifts. Teams reset. Then the same sequence plays out again.

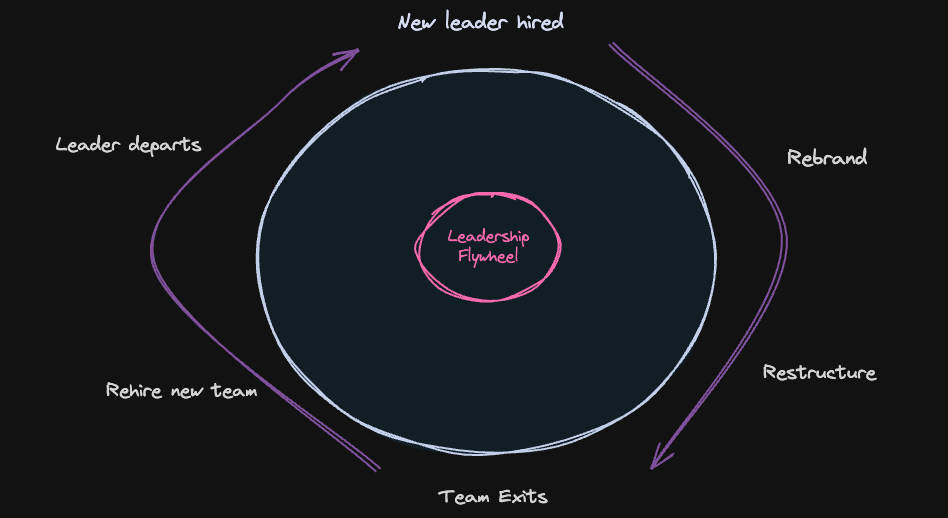

I don’t think this usually comes from bad intent. Leadership choices shape the outcome in systems that reward visible change over durability. Over time, I started thinking about it as a flywheel. Not a formal model, just a way to explain why the same behaviors reinforce each other and keep repeating.

A pattern I keep seeing

It usually starts the same way. A new leader joins with a mandate to fix things. Expectations are high, time is limited, and the organization wants to see movement quickly. There’s pressure to create clarity and confidence, both internally and externally.

That pressure shapes the first decisions. Change becomes the most visible signal of ownership. Direction gets reset, priorities get reshuffled, and the org starts moving before there’s full context on why things look the way they do.

What follows is consistent enough that it’s hard to ignore:

- A rebrand or reset of priorities

- A restructure to match the new direction

- People exit, sometimes by choice, sometimes not

- New roles open that look a lot like the ones that were removed

Within a year to eighteen months, leadership changes again. The next person inherits a partially reset system, and the cycle starts over.

The leadership flywheel, as I see it

I think of this as a leadership flywheel because each step reinforces the next. New leadership enters under pressure to show progress. Visible change signals momentum. Structural and team changes follow. Outcomes take time. Leadership tenure runs out before those outcomes fully materialize.

The flywheel keeps moving not because anyone wants disruption, but because motion is easier to measure than durability. The system rewards visible change more than sustained execution.

Why leadership transitions often start with change

From the outside, change reads as action. From the inside, it often reads as necessity. New leaders inherit teams they didn’t build and strategies they didn’t choose. There’s limited trust in inherited context and little patience for slow understanding.

Resetting direction, structure, or messaging establishes ownership and creates distance from what came before. The issue isn’t that change happens. It’s that change becomes the starting point instead of the result of learning.

What gets lost first

The earliest losses are quiet. Context disappears. The reasoning behind past decisions fades. Work that was in motion loses sponsorship and stalls, not because it failed, but because no one is left to carry it forward.

Each transition removes another layer of institutional memory. Over time, teams stop assuming their work will compound. They expect it to be revisited.

What gets lost over time

As these transitions stack, the cost becomes harder to ignore. Strategy turns into something that’s constantly reworked instead of built toward. Teams get cautious about long-term bets. Confidence in direction erodes, even when the direction itself is sound.

People adapt by narrowing scope and shortening time horizons. Not because they lack ambition, but because they’ve learned what survives resets and what doesn’t.

The professional impact no one plans for

Leadership transitions don’t just reset strategy. They reset careers. Performance gets evaluated by managers who weren’t there for the work. Progress has to be re-explained. Advocacy disappears when leaders leave, often through no fault of the people they supported.

Growth becomes uneven. Not tied to output or impact, but to timing. This is one of the harder realities to talk about without sounding bitter, but it shapes how people experience their careers more than most organizations acknowledge.

I’ve experienced this firsthand, including situations where positive reviews, bonuses, and pay adjustments existed right up until a leadership change reset the narrative. In those moments, the work didn’t suddenly stop delivering. What changed was how success was defined and which outcomes mattered.

A leadership assumption worth challenging

Teams often get labeled as underperforming when the real issue is instability. Work doesn’t fail because the people were wrong for the role. It fails because the system never gave it time to land.

Strategy gets blamed when continuity was the missing ingredient. Changing players is easier than stabilizing the field, but it rarely addresses the underlying problem.

Entering a team without restarting the cycle

There’s another way to enter an organization, though it’s slower and less visible. Spend time with the team before reshaping it. Separate inherited issues from structural ones. Learn what’s already been tried and why it stalled.

Most teams don’t need to be replaced. They need space to operate without being reset every year. This doesn’t mean avoiding change. It means earning it.

Living inside leadership transitions

For people inside the system, there’s no clean answer. Some leave early. Some stay and adapt. Some get reshaped into roles they didn’t come in to do. Occasionally, a leader arrives who builds with what’s there instead of tearing it down, but you can’t plan on that.

What you can plan for is the reset.

You shouldn’t assume your previous performance reviews will be read. You shouldn’t assume context will carry forward. You shouldn’t assume the work you did speaks for itself once the people who sponsored it are gone. That’s frustrating, and it’s draining, but it’s also the reality of how often leadership changes.

Writing things down helps more than people want to admit. Not as self-promotion, but as continuity. Capture what you worked on, why it mattered, what changed because of it, and what didn’t get finished. Keep a record of decisions, outcomes, and tradeoffs while the context is still fresh.

This isn’t about selling yourself constantly. It’s about not starting from zero every time the org resets.

Over time, these notes become your own internal handoff doc. They make transitions survivable. They give you a way to ground conversations when direction shifts again. They help you advocate for your work without relying on memory or missing context.

You can’t stop the leadership flywheel alone, but you can make sure it doesn’t erase your contribution every time it turns.